Two weeks ago, I traveled to Toronto’s far north for a lunch

presentation (recorded on video as part of the excellent IP Osgoode Speaker Series) from the Honourable Mr. Justice

Marshall Rothstein of Canada’s Supreme Court. Justice Rothstein was the author of

the dissent in the recent 5-4 SCC fair dealing decision that went against the

interests of writers and publishers, and is right now being broadly

misinterpreted by shortsighted educational administrations keen on saving

money.

Justice Rothstein was wise, charming and occasionally

hilarious in his presentation. “Everyone at the Supreme Court thinks they’re an

expert on copyright,” he quipped. On the topic of whether or not broad

unlicensed classroom copying has suddenly been legitimized by the SCC, he referred to his dissenting opinion in the Access Copyright case,

“private study couldn't mean hundreds of thousands of copies made across a province as part of an organized program of

instruction.”

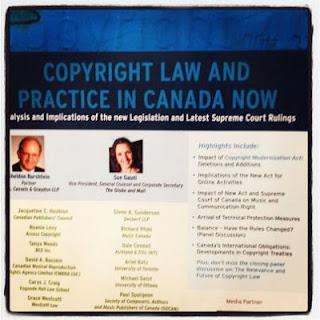

Last week, I attended a two-day conference in Toronto

examining recent changes to Canadian copyright law (including the SCC decision

above). The meetings took place in the steel and glass canyons downtown, were

filled to capacity with lawyers (and the occasional association executive), and

provided little assurance that the quest for a truly fair copyright regime for

the digital age is anywhere near over.

The one certainty delivered at the conference is that

everything about copyright is even more uncertain than it was before the

passing of Bill C-11, Canada’s Copyright Modernization Act. Key terms have been

left undefined, key meanings unclarified. It looks like Canada is headed into a

sustained period of legal wrangling over these terms and meanings – a period

that will further confuse the already confused, and cost absurd amounts of time

and money.

And speaking of money, I came away from that conference with

two key learnings about Canada’s freecult – those academic theorists railing

against copyright and the “legacy” rightsholders who insist on protecting it.

Firstly, they haven’t a clue about the real economy they are trying to disrupt,

and secondly, when they say “it’s not about the money,” everyone should fly to

Vegas immediately and place a very large bet on “it’s about the money.”

Ariel Katz, a law professor at U of T most famous (to me)

for his offensive tweets, drew a lot of shaking heads when he questioned

whether or not the Canadian publishing sector would even notice a loss of

collective licensing revenue (calculated loosely (very loosely) at about $40

million per year). Admitting that he’d not actually done any real research on

the question, Katz declared he’d taken a quick look at some earning statements

of large publishers and wasn’t convinced $40 million would be missed. That’s

right, to Canada’s freecult - all safely and comfortably tenured professors - $40

million is a trifle that no one in writing and publishing should worry our little

heads over.

Michael Geist, on the other hand, may have inadvertently

drawn back the freecult curtain with his unexpected admission that educational

administrations may not quite be the "freedom" fighters the freecult would like

them to be. In the middle of a predictable panel conversation about how

copyright disrupts educational access and the freedom of students to learn, I wondered

aloud if educational fair dealing is all about access and freedom, and not

really about money, why is there so much focus on how much collective licensing

costs (that insignificant $40 million again). Geist allowed that while students

and professors may focus on access, it is possible educational administrations do

consider the money to be an important factor. He then said something I found

startling.

Geist mused that educational administrations might be more

likely to sign collective licences if they were priced lower. Not at $20 per

student, is how he put it, but perhaps at $5 to $10 per student.

Strange... the new fair dealing policies being drawn up for

K-12 schools, colleges and universities around Canada are meant to be in place

of licensing, aren’t they? And they seem meant to declare that schools can now

depend on the law to excuse them from any price for those formally licensed

uses, don't they? That’s certainly the non-binding legal opinion Professor Geist has been

offering through his blog for months now, unless I've been reading him incorrectly.

Why would any school sign any licence at any price if the

law told them they didn’t have to? I mean

I know they still need to sign licences, I’m betting Justice Rothstein of the

Supreme Court of Canada thinks they still need licences, but a freecult leader

also admits the likelihood of licences while continuing to suggest they are unnecessary? How is that possible?

I think the answer is obvious. The freecult, with their

superficial grasp of cultural economics, and their loose analysis of actual

law, doesn’t have any idea what their advice will do for education. One

wonders, as well, if they care.

Tweet

2 comments:

A great piece of speaking sense to uninformed power. Thank you. I have posted it to my FaceBook page, and look forward to getting to know you as my TWUC Exec Direc. - George Payerle

Thanks for the comment, George. And I look forward to meeting as many TWUC members as possible.

What I really want to see more of going forward are individual writers like yourself speaking out publicly about your rights - even if it's only by commenting on blogs like this.

Too often, copyright is portrayed as a corporate luxury. People need to understand that it is the legal framework around a universally recognized human right for individuals.

Post a Comment